Home »

Content management in the museum

Digital content has become indispensable in museums. But what is the optimal way to create and post content when you need to coordinate different trades with each other?

These can be texts, images, videos, or audio recordings that run on dedicated players in the loop. This content must also be distributed and should be interchangeable at any time. In most cases, this is done using a file transfer, i.e. the content is copied directly to the playout systems (content push).

However, things get more complicated when this content is part of a larger interactive application. At the latest then one should no longer do without the use of a CMS. Because at that point, content exchange may become expensive. For example, if a programmer based in Munich has to recompile the application for a small text change and the application then has to be re-installed in Berlin. The applications should therefore be written or created in such a way that they fetch the content from a CMS server.

Content Management System — CMS is not just CMS.

CMS is not a protected term and simply describes the fact that somehow and somewhere content is exchanged.

But you should pay very close attention to your requirement. If you search for the term CMS on the Internet, for example, you will quickly come across the usual suspects such as WordPress, Joomla, or Typo3. There are now countless content management systems and each fulfills one or the other purpose better or worse.

For example, if you want to build a blog site, you are well served with WordPress and for a web presence Joomla or Typo3 are not a bad choice.

But what about when you have different interactive applications whose content you want to share individually — like in a museum, for example?

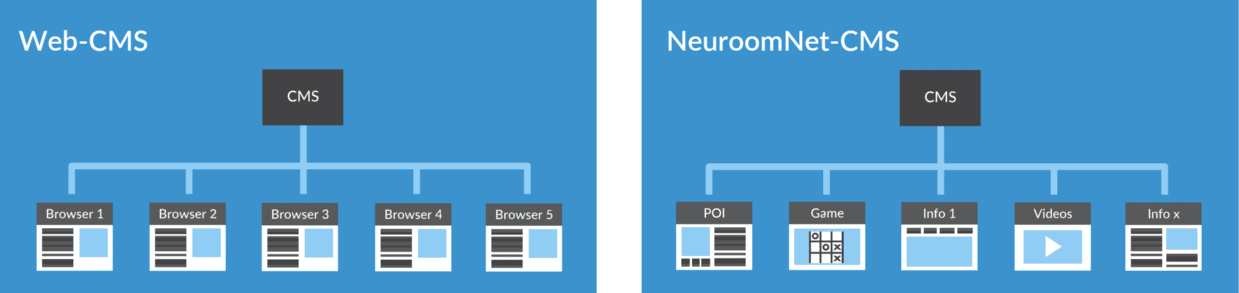

This is where the big discrepancy with the classic web CMS systems just listed becomes apparent. These systems are designed to create ONE source, for example, ONE blog with perhaps several sub-sites. This ONE source is in turn accessed by MANY devices, meaning many people look at this blog with their browser and it looks the same to every viewer. In this case, the CMS also determines how the content is displayed, as well as the behavior of the page.

This brings us to the second criterion. Because in the case of the museum, you have different applications, for example, a game, an information application, and a video slideshow. Their appearance and behavior should be different in each case, i.e. individually programmed. But all applications should get the data from ONE CMS. So the CMS should only provide content and not care about the appearance, but provide content for many different applications.

This type of CMS today rather falls under the term headless CMS. NeuroomNet includes such a CMS. This provides an API, i.e. a well-defined interface, to give programmers a uniform way of retrieving content from a central location, which can be changed by the museum at any time.

This circumstance should be taken into account, especially in tenders. Because if you expect only a CMS there, you might get one of the web CMSs mentioned above. These tools are mostly free to install but do not bring the desired functionality.

From the idea to the end product

Let’s assume that we want to have software written for a museum application. First, as with any good software, a specification sheet should be created, preferably with meaningful screen designs. But there the boundaries are fluid, whether you choose the classic path or more of an agile approach.

However, if you plan to exchange or add to the content at a later date, you should already be reasonably clear at this point about what content this concerns. For example, if we have an application that lists all Nobel laureates with corresponding additional information, we also want to be able to add new scientists. But if you write “All content should be exchangeable via a CMS”, you have on the one hand the problem that the CMS is not defined (see above), and on the other hand that for the programmers also the graphics on the buttons or the background graphics or labels of buttons are content. You may want to share that content as well, but if you don’t, it just drives up the cost.

When will the data come?

Done, done, agreed. The programmers can start working. In parallel, the content is created. No problem, the programmers can already work with dummy data. Sure, they can. But good, if formats are already clarified at this point. Surprises like “Oh, but the pictures are big/small” or “.doc files we can’t read in” — Nobody needs that and usually lead to more costs on some side.

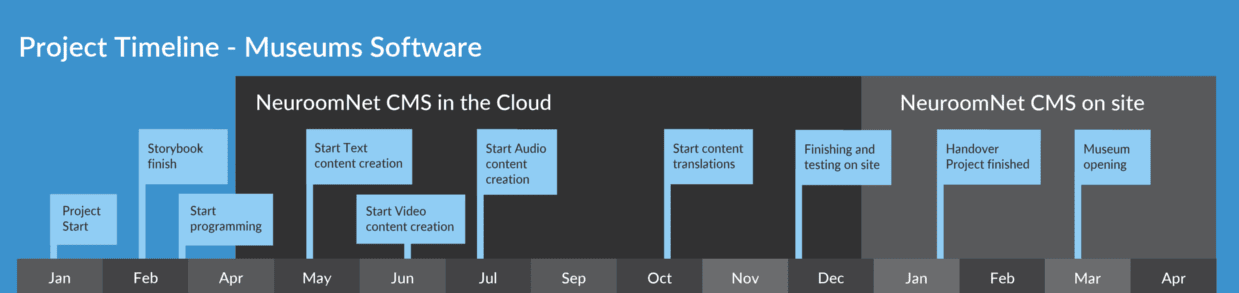

Lucky who can already access a CMS at this point. When the CMS is running in the museum’s IT, programmers, translators, graphic designers, etc.“only” need a VPN to access the same data as the scientists and museum staff working internally.

In practice, things usually look different. Then, for example, when the museum is still under construction or reconstruction. Or at least the IT has to be retooled accordingly, or, or, or.…

Therefore, let’s focus on the most relaxed of all solutions. NeuroomNet hosts the CMS online for them during the development phase. All participants use, create, and correct the same data from the beginning. Problems like too big, too small, too much text, and too little, are noticed immediately and not when the application is ready. At the end, when the application is installed on-site and NeuroomNet provides the CMS locally in the museum, NeuroomNet simply moves the data to the local museum IT.

In an “all-around happy package,” we accompany you from consultation, planning, hardware procurement, installation, configuration, and commissioning to documentation and training of your staff.